I wrote this piece in 2007 while researching an article on jigsaw puzzle-making for New England Watershed Magazine. “Puzzle Benders” appeared on my weblog New England Watershed in 2010.

I wrote this piece in 2007 while researching an article on jigsaw puzzle-making for New England Watershed Magazine. “Puzzle Benders” appeared on my weblog New England Watershed in 2010.

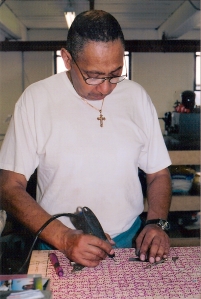

CARLTON HERRING BEGINS his day at Garofalo Dies at 6:45 a.m. on the fifth-floor loft of a warehouse at 488 Morgan Avenue in Brooklyn. With rows of tall windows on either side, the room has commanding views of Brooklyn and the Manhattan skyline, but Herring rarely appreciates it. For most of his eight-hour shift, his head is bent over an intricate puzzle grid on wood, which he painstakingly recreates in one-inch strips of steel.

Herring is one of the last remaining craftsmen in a die-making world that has become almost totally automated. So far, the idiosyncratic shapes of jigsaw puzzle pieces have eluded mechanization, leaving a handful of men to spend their days tapping out exact replicas in metal so manufacturers can make up to a quarter-million “kiss cuts” on chipboard, each one resulting in a new puzzle.

Herring, 67, has lived most of his life in Brooklyn. A big man, tall and soft-spoken, he was trained as a die-maker in 1965 under the Manpower Development and Training program for unemployed workers started by President Kennedy in 1962. For the next 30 years Herring made dies for all kinds of products at Block Dies in Brooklyn. When the company moved to New Hyde Park in 1995, it was too long a commute for Herring. So he stayed in Brooklyn and became a puzzle bender.

When offered the opportunity to learn how to bend puzzles, he initially declined. But it paid $5 more per hour than the work he had been doing, so he decided to give it a try. “I thought it would be tedious,” he says. “But I enjoy it. I know what I have to do, and I do it.”

Now, “I can look at a puzzle and know exactly how long it will take me, regardless of what I have to do on it. It’s a lot of work, but I enjoy it.” The 1,000-piece puzzle he was bending in June “takes about five weeks, from start to finish.”

The hardest part of the job is standing all day, but Herring has no plans to stop working anytime soon. “At one point talk of an automatic bender put a scare in me, but it won’t be happening anytime soon. This will last my lifetime.”

While bending puzzles remains a craft, “a puzzle within a puzzle,” says Mark Lambert, who purchased Garofalo Dies in 2006, the process is computerized at the outset. Diecutting Tooling Services (DTS) in Holyoke, Massachusetts, which Lambert also owns, receives Computer Aided Drafting (CAD) files of designs from its clients, which include puzzle-manufacturing giants Edaron (a subcontractor for retailers like Barnes & Noble, Wal-Mart, and the games company CEACO) and Hasbro, owner of Milton Bradley, the world’s leading producer of puzzles and games.

The pattern is laser-burned into a thick board at DTS’s Holyoke plant, and the board is sent to Brooklyn, where Herring, an apprentice and two other die-makers begin their craft. The work is done in short sections, a few inches at a time, and the die-maker must calculate for the “bridges” in the laser board that keep the puzzle grid intact — without them, the pieces would fall out.

Each strip is labeled with coordinates corresponding to the laser board’s map-like grid (A21, B18 and so on), and the finished sections are marked off with a colored marker so the puzzle bender knows which areas remain to be done. The bent strips, tapped out meticulously by Herring on a die-making machine, sanded and trimmed for an exact fit, are thrown haphazardly into a cardboard box with dozens of others.

When he needs a break from the demands of this work, Herring takes the completed sections and inserts them in the emerging die using a mallet, pliers and the numbering system to find the right location. The finished die resembles a large and intricate cookie cutter.

While the designs are unique, each puzzle manufacturer has its own style. “It’s not exactly a patent,” says Lambert, “but Milton Bradley has formalized their style, as has Edaron. Edaron is one of the hardest because they have so many back-bends in their designs.”

Only a handful of companies still make dies for jigsaw puzzles; Lambert estimates there are fewer than five in the country. Aside from being a specialty, there simply is not enough puzzle business to go around. Lambert figures only 10 percent to 20 percent of his small company’s business is in puzzles. His other employees spend their time making dies for carton manufacturers for such products as cereal boxes and auto parts.

Jigsaw puzzles are thought to have originated in England and Europe in the mid-1700s, and were at first primarily educational and for children. The earliest American manufacturer, according to Anne D. Williams in The Jigsaw Puzzle: Piecing Together a History (2004, Berkeley Press), was Andrew T. Goodrich of New York City, who declared in the January 7, 1818, New York Evening Post that they had “completed a new and elegant Dissected Map of the United States, which has long been a desideratum in this country for domestic instruction and juvenile improvement.”

Milton Bradley’s success with puzzles began in the 1870s with “Smashed Up Locomotive, A Mechanical Puzzle for Boys,” which featured 56 non-interlocking pieces in shapes like squares, triangle and oblongs.

It was not until the recession in 1907 that puzzle-making took off as an adult activity. Jigsaw puzzles are, in fact, recession-proof: when the economy goes bad, people are more likely to stay close to home and seek inexpensive entertainment. The other big puzzle craze of the last century began in 1932, at the height of the Depression. In a good economy, manufacturers experience steady growth.

Yet puzzle benders “are a dying breed,” says Marty Rand Sr., 70, a former manager at Garofalo. He taught Herring and others over the years. “Unless someone teaches you, there’s no way to learn it,” Rand says. “It’s not a natural thing.

“Everyone’s trying to find a way to automate the process. But the nature of the beast it that not everything is the same shape or size. The human element ensures that every piece is unique.”

Rand was a general die-maker for years before he learned to bend puzzles. “I could bend steel rules real well, so I thought it would be easy,” he says. “But it took me two hours to make my first two loops. Now I do about a loop a minute — and I may have slowed down a little. It’s like riding a bike. Once you get it, you don’t forget it.”

Rand started as a deliveryman for Tru-Line Dies in New York in 1958, and stayed for 11 years, trained first as a die-maker, then in the drawing department. “This was before Computer Aided Drafting,” he says, “you had to draw everything out by hand.” He then went to work for De Larosa Steel Rule Die, and that was where he learned to bend puzzles for Milton Bradley.

“Some guys could bend your profile just by looking at you, or the face on a dime,” he says of the men who taught him. “We used to make a snowflake out of all one piece. If you are a die-maker, there is nothing you cannot do.”

New York was “the die-making capital of the world” in those days, he says, from Greenwich Village to 26th Street, and remained that way until the 1980s, when competition from places like China and Mexico began to erode the United States industry. Despite this, in 1980 Rand started his own company, Greater New York Steel Rule Die, which stayed in business for 22 years. Their work included puzzle dies but “we did everything,” he says, at a time when “automation was just a gleam in people’s eyes.”

Bending puzzles “is like therapy,” says Rand. “After awhile, you don’t even have to think about it, you can let your mind wander to whatever problems you’re facing.

Hello! I love puzzles and I have been dreaming of starting a small puzzle company but I can’t find a rule bender! I read this article and feel there could be hope or am I dreaming! Help!

That’s great, and good luck. I doubt if Carlton is still working, but perhaps the company in Holyoke he worked for is still in business. A rare skill!