EXCITEMENT IN HATFIELD! On Molly’s first day back from camp, she battled a woodchuck. Both survived (or so I believe). The woodchuck fared worse and probably spent a sore night, but still managed to bite Molly’s lip during the fray.

The confrontation was unavoidable, similar to the time last summer that a young rabbit practically ran into Sadie’s mouth as she ran along with her nose to the ground (Molly’s friend Sadie, a Brittany Spaniel, is a frequent walking companion). Yesterday Molly and I had just left the pavement leading to the farm roads, where she can be off leash, and she bounded ahead past a tobacco barn not 20 yards ahead. In the field beyond, the woodchuck sat close to the road in plain sight, so near our path that Molly would have had to have been deaf and blind to have missed it.

EVEN MICKEY, my black lab, would have been hard pressed to have avoided a stare-down. Mick was the most peaceful dog I have ever known. He would not even chase squirrels (one of Molly’s greatest passions). During Mick’s one encounter with a woodchuck in my back yard, he merely stood and barked at it a couple of times, a rare occurrence for him — he probably barked less than 50 times during the entire eight years I lived with him. I suspect his bark translated into something like “Run!,” as he stood unmoving while the woodchuck scurried away.

This was in stark contrast to my childhood dog, Waggie, a collie mix who was relentless in her pursuit of woodchucks, killing eight or nine annually in our fields, much to the approval of the farmers who rented the land to grow alfalfa and hay. The farmers even sent a shadowy figure known to us boys simply as The Woodchuck Man several times every summer to reduce the marmot population. He was a soft-spoken, amiable man, wearing a broad-brimmed felt hat and cradling a shotgun under one arm and carrying a satchel with several small canisters that he would drop in the woodchuck holes to smoke them out.

I may be imagining this, but my lasting image of The Woodchuck Man is in a black shirt or jacket. He would smile and say hello to us when he arrived, but then he was off into the fields, and we did not see him again until his next visit, although we occasionally heard the distant report of his gun.

To the average person, a woodchuck is relatively inoffensive — certainly much preferable to ticks and mosquitoes, if rather dull and ugly, and partial to tender, young garden vegetables. But to a farmer, woodchucks can be a real nuisance. They dig their random burrows in the middle of fields, where the soil is soft, the food abundant, and the cover plentiful. To the narrow front wheels of a tractor or the even smaller ones of a hay rake or baler, the holes represent a significant and potentially dangerous hazard, capable of twisting or snapping metal machinery or suddenly jolting the tractor in a new direction, whipping the steering wheel from the driver’s hands. Hence The Woodchuck Man.

Molly is normally a peaceable dog, like Mickey; except for the rabbit she has mostly pursued partial, foul-smelling carcasses (the squirrels are a game or irritant, I think, rather than genuine objects of malice). Molly did catch a female pheasant once, but the bird appeared to be mentally or physically deficient. Then Molly did an odd thing, trotting out into the middle of a field and giving the pheasant a decent burial before rejoining me on our walk.

Wednesday’s battle lasted only a few minutes. Trying to spare both dog and woodchuck, I folded Molly’s leash in half and swung it ineffectually between the two, but rather than the desired effect it merely added to the frenzy. Molly yelped when the woodchuck got in its bite, but otherwise, taller, faster, and four times the weight of the marmot, Molly had little difficulty lifting it in her mouth and shaking it furiously before dropping it.

This happened several times before I decided my best strategy was to walk on. Molly, a rescue pup, hates to be left behind, and I knew from my experiences with carcasses that any attempt on my part to take them from her provokes a primal flight response, a sign to her, apparently, of the thing’s value. For better or worse, the two animals would have to work it out on their own.

A MINUTE OR SO later I looked back, and Molly was standing in the knee-high grass on the other side of the road, sans woodchuck, searching. I suspect that the squirming thing was too big and heavy for her unpracticed jaws and she dropped it, and once in the high grass the woodchuck knew what to do to make its getaway.

Molly several times looked back and forth between me and the enfolding grass, trying to decide her course of action. Eventually she relinquished the hunt and started after me, stopping once or twice to look back as if reconsidering. Soon she was on to tamer amusements.

She was more interested in the excitement of the chase, I think, rather than killing, and — though perhaps I anthropomorphize — being bitten may have even triggered a kind of empathy with the woodchuck. Her reaction did not appear to be one of increased anger, or caution, or fear, and the confrontation ended soon after. Molly is best friends with a swashbuckling cat named Teddy, and their play is often rough and physical. It may be that the woodchuck’s bite reminded Molly that excessive force can unintentionally hurt either party.

Still, when her legs are twitching in sleep tonight and she lets out a few muffled squeals, I suspect she will be reliving the scene in her dreams. After food and love, for a domesticated dog it does not get much better than this.

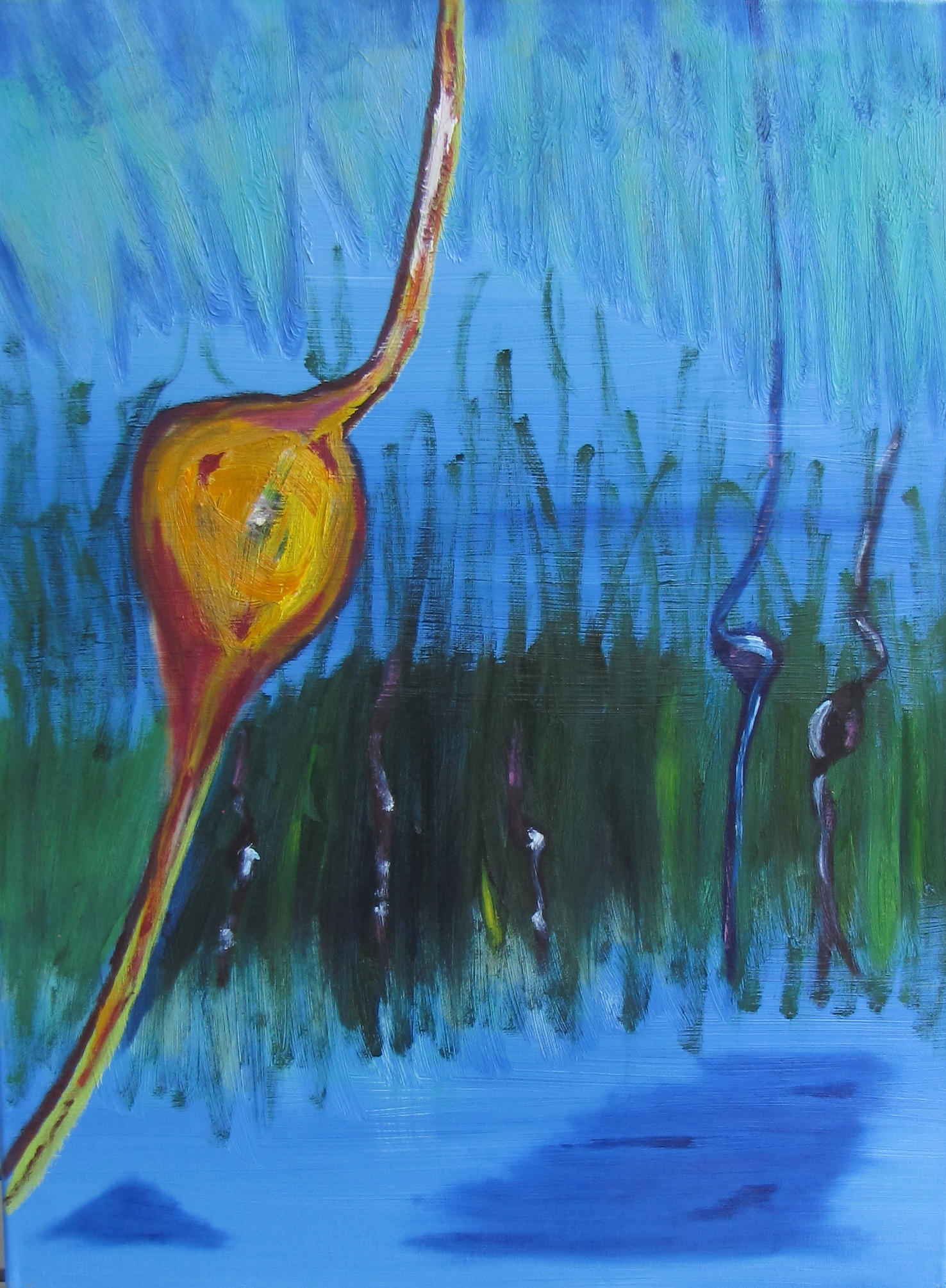

“How much wood would a woodchuck chuck if a woodchuck could chuck wood.” That is what came immediately to mind when I saw the title of your painting. I then looked up the word “chuck” and saw that its general meaning is to toss something away. Do woodchucks toss wood away? I thought your essay today was fun. We all love animal stories. My Hudson, the bigger of my two rat “terrors,” one day confronted what I assumed was a badger down by the river. I had to see what he was barking about so I walked down the path and suddenly saw a furball tear off across the field. It’s neck was spotted with blood. I wanted to stop Hudson from killing his prey, but then thought this is mother nature at work. Hudson was acting instinctually. So I walked away, not wanting to view the carnage. I don’t think Hudson got him since pretty soon he was walking with me. But it was quite stunning to see my playful, affectionate Hudson become a would-be killer.

Thank you Damaris. Even the tamest of our pets, it seems, still smells blood (except for Mickey)!