LOOKING BACK, one of my earliest jobs was one of my fondest. Perhaps it is nostalgia for a dying profession from a bygone era. I was a milkman.

Coming out of college in 1976, I was clueless about a career. An English major, I wanted to write, but creative writing only — poetry and fiction. I wasn’t about to stoop to something as pedestrian as journalism.

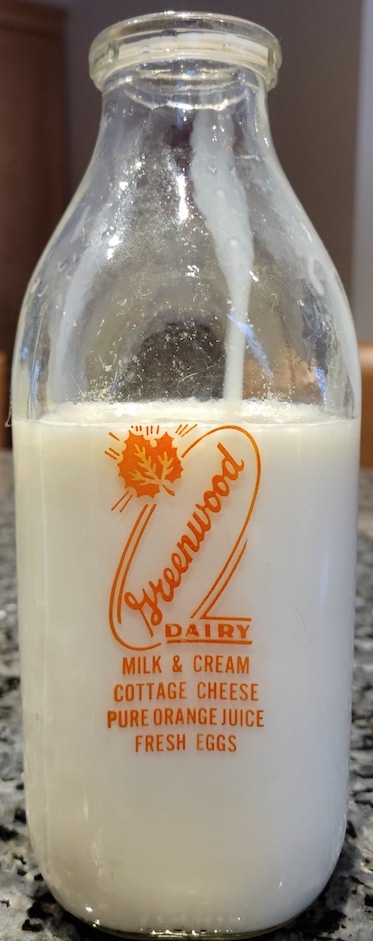

Yet, newly married and renting a small bungalow, I needed a job. So I answered an ad for Route Sales for Greenwood Dairy in Worcester, Massachusetts. It didn’t pay much but was steady.

The job appealed to me. I had been around cows my entire life, at my grandfather’s and then my former father-in-law’s farms. Both raised Jerseys, those sweet, honey-brown cows whose milk has exceptionally high butter fat.

I worked at a local dairy farm, milking, feeding, and cleaning up after a herd of black-and-white Holsteins and a few brown-and-white Ayrshires several summers during and after high school, the latter well into the fall. Delivering milk was familiar and wholesome (and clean).

My interview was brief, straightforward, and seemed to go well, although, Ray, my would-be boss, said that he didn’t like drivers with facial hair (at the time I was sporting my one-and-only moustache, a thin, forgettable thing).

I took the hint, and when he called me back, I had already shaved it off. I wanted that job. Ray didn’t notice at first; he planned to hire me anyway. But he smiled slightly when he realized what was different about me from our first meeting.

* * *

I WAS GIVEN TWO BLUE SHIRTS with Greenwood Dairy stitched above the pocket in bright orange thread, and a thick, warm bomber jacket, also adorned with the dairy logo. (I coveted that jacket and hoped to have it for all time. But when Ray asked for it back after a few weeks after I quit, I couldn’t refuse him. The dairy was hurting, and I knew it.)

For the next 14 months (with a single week for vacation), I rose at 5 a.m. five days a week and drove approximately 12 miles from our home in Spencer to the dairy on Greenwood Street in a residential neighborhood in Worcester, regardless of weather. People needed their milk, rain or snow.

On the ride in, I tuned the AM radio to 1010 WINS news from New York City with its iconic jingle and slogan, “You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world.”

I couldn’t get reception any other time of day. Listening made me feel connected to a larger world beyond my tiny speck of the universe, member of a small society already at work while others slept. I felt that way years later delivering Sunday newspapers.

I left home in the dark in my 1965 Valiant, rust bleeding through each side of its powder-blue hood, and returned home by early afternoon after finishing my route in Grafton or Oxford. I traveled those roads so many times I would probably still recognize some of those streets and houses now, nearly half a century later.

Arriving at the dairy at 5:30, I loaded my truck, unplugged the refrigeration unit, and checked my notes for changes to the day’s deliveries. Directions were efficiently laid out in stacks of well-worn flip cards on metal rings that could be unclasped to slide in new cards or remove old ones.

Each card had the customer’s name and a product list with their standing order. At the top, drivers penciled in directions from house to house, like “L-L-R-L” “# on mailbox,” or “R at stop sign, blue with fence.” My all-time favorite ended with the crude but apt, “shit brindle on L.”

The truck interior was spare. I sat behind the steering wheel on a tall swivel stool. The narrow folding doors on either side opened like a school bus (I kept them open in good weather). Beyond the stick shift to my right was a freezer compartment for ice cream. A metal mesh rack above my head over the dashboard held loaves of bread.

At each stop I pulled the hand emergency brake, pivoted on my chair and pulled the handle on the refrigerated compartment right-to-left in one motion. I filled the metal basket resting on the neat stacks of milk cases with the next order: two quarts skim, one half-gallon whole, a pound of butter, and so on.

The milk was identified by the color of its crimped paper cap: red for whole milk, yellow for low-fat, lilac for skim, green for non-homogenized (with a thick layer of cream at the top). I also carried bread, butter, cheese, eggs, ice cream, and orange juice, and a sweet, bland drink called Orange Spot.

The glass quart and half-gallon milk jugs were placed in slotted metal crates and stacked in two layers in the truck. Returning empties gradually refilled the crates, and I occasionally stopped to rearrange them at the back of the truck, sliding the full crates forward.

* * *

GREENWOOD DAIRY had eight drivers in all, but I didn’t really get to know them. We didn’t spend much time socializing. We wanted to get to people’s homes early, in case they needed milk or eggs for breakfast. Ray encouraged us to take our time and sell some of the extras in our truck. But most of us did very little selling and were in a hurry to get done.

One driver complained that his truck kept getting broken into while he delivered milk to apartments in the upper floors of a Worcester apartment building. Thankfully I had no such problem on my suburban route.

Ed, an older driver, a smoker with slicked-back white hair, was the antithesis of me, lingering for hours at a diner on Main Street in Spencer, where his truck was parked well after the rest of us had finished our routes and gone home. I never knew if he was trying to make it look like he was more conscientious than the rest of us, or if he simply enjoyed himself and had no better place to go.

A middle-aged man with a chipped tooth and thick black hair cropped close (also named Ray), filled in wherever needed when someone was sick, didn’t show up, or took the day off. He was close with the owner and knew all the routes — and ropes. He gave good advice and carried himself with a bit of a swagger.

I was always in a rush to get done. I justified it because of the low pay, and at times to see if I could beat my previous times. Yet most mornings I stopped for raisin toast and coffee at a breakfast shop in Auburn, where the proprietor, a tall, thin man with wireframe glasses, salt-and-pepper brush cut, and a thick German accent regaled his elderly regulars with the day’s news. I eavesdropped as I drank my coffee, scribbling poetry on a napkin.

A mechanic was always on duty. The fleet of emerald-green milk trucks was ancient, and always breaking down. One morning as I was speeding along on a two-lane highway, approaching an intersection where I needed to make a right-hand turn, I discovered that my brakes were gone.

I had little time to act. I downshifted quickly and swerved into the corner lot of an empty gas station, metal racks and glass bottles rattling behind me, then downshifted again and, bracing myself, made the hard turn right into the road. The load shifted and made a racket, but fortunately at that early hour no cars were coming, and not a single bottle broke. But I had to call in for another truck, and I shook for the rest of the day.

Another time I skidded into a tree after a snowstorm. I wasn’t hurt and the damage to the truck was minor, but I was miles away from the dairy, and I had to sit in the cold truck for the hour it took for the mechanic to finally reach me. More delay! The dairy had to send another truck, an even older one this time without refrigeration, and I had to finish my route with Ray, the jack-of-all-trades, driving.

The challenges weren’t always mechanical. One cold winter morning I discovered that the back door of my truck was iced shut when I went to reorganize the crates. I yanked on the handle and punched the door, to no avail.

Desperate, I remembered I had an old newspaper in front, and matches. I rolled the newspaper lengthwise and lit one end, holding the sudden flame beneath the handle. I yanked and punched again. Still nothing, and my hand was beginning to hurt from the pounding.

Managing to prop the latch in the unlocked position, I returned to the cabin and climbed inside the small door leading to the refrigeration section, crawling over the metal cases in the dark until I reached the back. Shifting my position so that I faced the inside of the door feet first, I kicked it with my boots as hard as my position allowed. Boom! It popped open.

* * *

FOR THE MOST PART, though, delivering the milk was an enjoyable job. I was outdoors and independent. Best of all I was home by midday.

I saw a number of new neighborhoods, met interesting people: the schoolteacher who occasionally invited me in for coffee, the poor, elderly couple who often sat outside eating lunch at a rustic table in their shady dirt yard until one summer day the woman announced, matter-of-factly, that her husband had died “just like that, eating a tomato sandwich.” She still ate her lunch under the trees but cut her order.

In many cases I never saw the customer, leaving the delivery in an insulated metal box on the porch or, in a few instances, walking straight into the kitchen and putting the milk directly in the refrigerator, per instructions. There were a few dogs I had to avoid, glad I had my metal basket.

Despite the jokes about milkmen, I never had even the hint of a morning tryst. The closest I came was a young mother in a modest pink bathrobe who talked with me occasionally while fixing her children breakfast. Hardly the stuff of romance. In any event, I was more interested in getting home than attempting to play Romeo.

* * *

IT WAS THE THREAT of winter weather that eventually got me to quit the dairy. It wasn’t just sliding into trees or unsticking frozen doors that bothered me, or even driving through snowstorms in the pre-dawn to get to work on time, although I had a few hairy commutes.

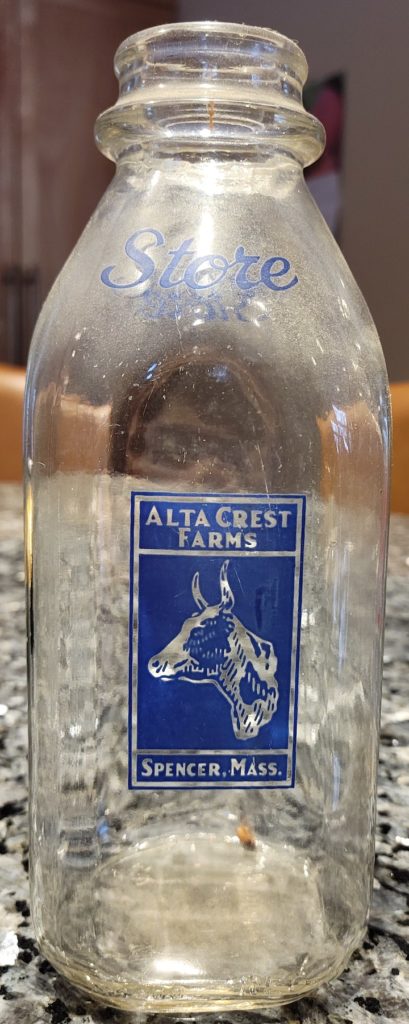

I compared notes with Bob, my father-in-law, who as a young man also delivered milk, for a dairy in Lebanon, New Hampshire. He was responsible for collecting money, and he recalled how people would drop their payment inside a milk bottle. Coins would freeze to the bottom on a frigid winter’s night, and Bob would have to bring the bottle to his truck and warm it up enough to loosen the change before he could continue.

Collections were more genteel in my day, but still added time to the route. Most customers paid the dairy by mail by then, and I didn’t have to deal with frozen coins. But I remember having to shake rolled-up dollar bills out of bottles, smelling of sour milk.

When I was a boy, my three brothers and I drank lots of milk. We had a friendly milkman named John, with a kind face and rust-colored glasses that matched the furrows of his neatly combed hair.

Twice weekly John brought us two-and-a-half gallon plastic containers with molded handles and red spouts. His beige-colored Hood truck would drip melting snow in our driveway and make clicking sounds while he delivered our milk and chatted briefly with my mother or brothers, sometimes returning to his truck for an extra loaf of bread.

Most customers received smaller deliveries than ours in glass bottles, which John loaded in his metal basket just as I did years later. One winter, John abruptly disappeared, and we later learned that he had taken a fall on ice while carrying a full basket and had been badly cut with glass from shattered bottles.

He never returned, and the image of him lying in spilt milk with slashed hands and wrists stayed with me as I approached my second winter with Greenwood Dairy.

Journalism never looked so good.

Russell – my father’s family ran the Rider Dairy in Danbury, CT and he told many similar tales. The driver’s seat in their milk trucks tipped forward and one time, when my father stopped short, all the milk crates slid forward, tipping the driver’s seat forward , and he had to be extricated by a passerby! I enjoyed your story.

Great story! I guess for some of us it is not such ancient history. Have you saved any bottles from your Dad’s dairy? Glad you enjoyed this and thanks for the comment.

I truly enjoyed reading this piece, Russell, and had remembered that you had this job but without any understanding of the rich details. What a wonderful storyteller you are!

Thank you, Elena! A memorable experience from a long time ago. I appreciate the kind words and encouragement!

A New-Yorker-worthy account/reflection Russ! Loved it!!!

High praise, Terri! Many thanks. So glad you enjoyed it.

I loved this story of your milkman experiences. It is so rich with details of the inside of the truck and the outside driving. This brought back childhood memories of our milkman in the 1940s in our Midwest town. We had an exterior milk-shelf with a door, built next to the back door on our newly built modern house just for our bottled milk orders. Unfortunately those deliveries stopped within a few years.

Thank you for a lovely comment and a wonderful memory. A good reminder of how things change!

I loved reading this, it was so engaging! I felt the cold wind in the open truck window, the icy bite of the bottle and metal baskets, and the slick walkways up to the houses.

We get a little of that old-fashioned connection to our food when we go to Uppingil and get our non -homogenized milk in glass bottles that we have to return. (Wouldn’t it be nice if they delivered them, umm, no, I don’t think that will happen.)

Thanks for sharing this with us, Russell

Thank you, Christine. A world ago! For a time Mapleline in Hadley made home deliveries, but I don’t know any place that does it now.