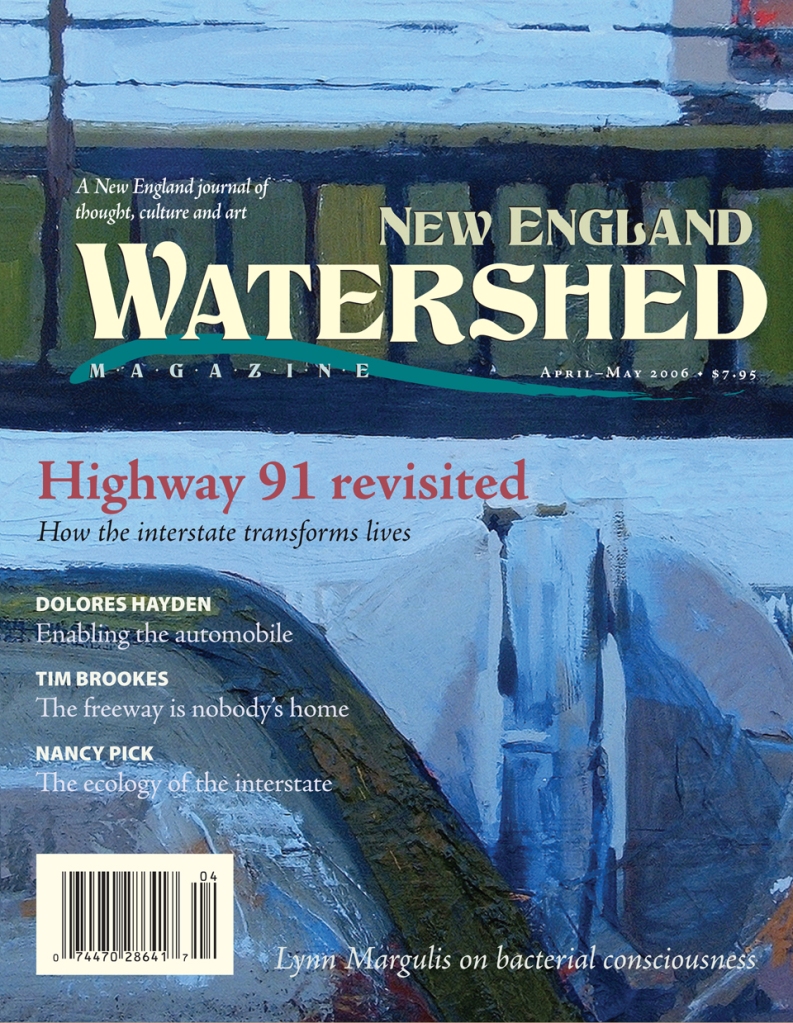

Where the rubber meets the road

BY RUSSELL POWELL

I AM A CHILD OF THE INTERSTATE. For most of my existence, I-91 has been as much a fact of life as the Connecticut River it parallels, or the Hartford, Connecticut, high-rises and Hartford, Vermont, mountains that loom above its path. Human and natural history eventually may reduce the interstate highways to rubble, but in my brief time on this planet, they are eternal.

Interstates are the new glaciers. Their impact on the environment is deep, slow-moving and profound. Their detritus is messy, and they are impossible to ignore. Yet it is remarkable how the highways’ ponderous bulk orchestrates movement. As a result of the interstates, I am connected to 48 states, east, west, north and south, through places urban and pastoral that otherwise I would never see.

Compared to the Internet, interstate highways are parochial and dull. Yet roads require real time and space, providing a physicality that I am loath to surrender as a thinking, breathing human being. There is something wonderful—and detached—about being in Tibet or Venus on a computer screen in the blink of an icon, or hopping on a jet and arriving in Paris just hours later (and into the following day!). Speed is best appreciated through contrast. We live on a planet, with hills, rocks, water and weather, and to subvert these undermines the meaning of air travel or cyberspace.

A glacier is to the river is to the interstate is to the Internet. Each has its time and place. We can’t truly know western New England without considering glaciers or the Connecticut River. We cannot understand contemporary American life without acknowledging its interstate highways. We cannot adequately prepare for the future without grasping the Internet’s vast potential. As part of the human condition and despite our short lives, we must ponder our place in the history of life on the planet. How will future generations remember us? What kind of world do we bequeath them? What, if any, will be our impact?

The interstates have driven us further apart and brought us closer together. From where I sit in western Massachusetts, Hanover, New Hampshire, and New Haven, Connecticut, have never been nearer—only an hour-and-a-half away. I traverse former fields, forests and neighborhoods to reach these destinations, but this greater access to place has enriched my life. The experiences of swimming in the ocean or skiing down a mountain, viewing rare works of art or receiving timely medical attention are no longer exceptional or mutually exclusive.

I rue the cost of this extravagance, in energy and pollution, in the slow killing of a previous way of life. But not enough to keep from driving. The interstate expands my possibilities for employment, entertainment, education, recreation. So does the Internet. Still, I like seeing and smelling the earth—even diesel. It reeks with consequence.

I rue the cost of this extravagance, in energy and pollution, in the slow killing of a previous way of life. But not enough to keep from driving. The interstate expands my possibilities for employment, entertainment, education, recreation. So does the Internet. Still, I like seeing and smelling the earth—even diesel. It reeks with consequence.

Each new technological advancement brings virtues and vices. The interstate displaced and isolated people and requires obscene amounts of resources. But its impact is felt and visible. The dead deer on the side of the road, the wavy salt lines of winter, rush-hour traffic, the empty fuel gauge, all communicate the price we pay to reach ski slope, office or arena. There are no tolls on I-90 (the Mass. Pike) from Springfield to Stockbridge, but I am still required to hand over a paper ticket to another human being; heading east on the Pike, I literally pay to drive. However mixed, the interstate offers context and meaning.

The Internet does not. It hides its physical and psychological costs. It is quicker than the interstate and its reach is global, but how the Internet connects us remains an abstraction. Like many facets of modern civilization, from cell phones to ATMs, the Internet’s brilliance is compromised by its detachment from time and place. As Gertrude Stein famously said, “There is no there there.”

I am no champion of the interstate. I can’t imagine what motivated anyone to build a towering garbage dump at the gateway to Hartford. I am amazed at the brazen marketing of the sex trade in Connecticut, whose billboards trump restaurants, healthcare, car dealers and higher education in this dubious claiming of shared views for corporate gain. I mourn the loss of the corner drugstore and precious orchard.

But I love the vistas of the Connecticut River and the Green and White mountains from I-91 and I-89. I admire the panorama of Holyoke, Chicopee and beyond from the vantage of a highway on which thousands of people commute to work every day. I share the intrigue around Samuel Colt’s onion dome in Hartford with countless drivers, and the familiar sight of Harkness Tower in New Haven before 91 merges with 95.

Let us critique the interstate, its faulty foundation and fragile future. But while it is with us, let’s celebrate the landscape it cuts through, en route to destinations previously beyond our reach.

The glaciers were cold; highways are hot. Heat cures—and burns. Until they are cinders, we will travel the interstates. As we develop alternatives, may we continue to value the passage of time and the meaning of distance and space.

Russell Powell is editor and publisher of New England Watershed.